Fresh DNA evidence reveals Napoleon’s troops were ravaged by paratyphoid and relapsing fevers during the 1812 retreat.

When Napoleon’s Grand Armée limped out of Russia in 1812, it wasn’t just the snow or the Cossacks that killed them. It was hunger, exhaustion and, as scientists have now discovered, a pair of microscopic assassins hiding in their bodies.

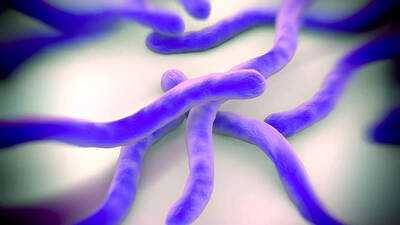

A new study from the Institut Pasteur has found that soldiers buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, Lithuania, carried Salmonella enterica, which causes paratyphoid fever, and Borrelia recurrentis, responsible for relapsing fever. It’s a small discovery, but it helps answer a big question: how did the most powerful army in Europe collapse into a ghost march of corpses?

The researchers used shotgun sequencing, a modern genetic technique that scans DNA fragments for matches with hundreds of known pathogens. Out of 13 soldiers studied, four were infected with paratyphoid and one with relapsing fever. One man may have suffered both.

Earlier studies, done with older methods, had blamed typhus and trench fever. But this new analysis paints a broader picture of disease and despair. Contaminated food and lice likely spread infection among men already half-dead from frostbite and starvation.

“In light of our results, a reasonable scenario for the deaths of these soldiers would be a combination of fatigue, cold and several diseases,” said study author Nicolás Rascovan. “While not necessarily fatal on their own, these infections could have been devastating for already weakened individuals.”

The team confirmed their findings through multiple checks, including signs of DNA decay typical of centuries-old remains. It wasn’t just science for science’s sake; it was a forensic reconstruction of human misery.

Historians have long argued over who or what defeated Napoleon. He blamed the winter. The French called it bad luck. The Russians called it strategy. Dr Michael Rowe of King’s College London thinks it’s time to give the Russians their due. “It wasn’t just the cold,” he said. “They had a good plan, clever manoeuvres and a capable army. Disease and weather only finished what their tactics began.”

So perhaps the real story of 1812 isn’t of heroism or hubris, but biology. The emperor who once thought himself invincible was undone by lice, bacteria and a few unlucky meals. The retreat from Moscow wasn’t just a military failure — it was a reminder that even empires, like men, rot from within.

When Napoleon’s Grand Armée limped out of Russia in 1812, it wasn’t just the snow or the Cossacks that killed them. It was hunger, exhaustion and, as scientists have now discovered, a pair of microscopic assassins hiding in their bodies.

A new study from the Institut Pasteur has found that soldiers buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, Lithuania, carried Salmonella enterica, which causes paratyphoid fever, and Borrelia recurrentis, responsible for relapsing fever. It’s a small discovery, but it helps answer a big question: how did the most powerful army in Europe collapse into a ghost march of corpses?

The researchers used shotgun sequencing, a modern genetic technique that scans DNA fragments for matches with hundreds of known pathogens. Out of 13 soldiers studied, four were infected with paratyphoid and one with relapsing fever. One man may have suffered both.

Earlier studies, done with older methods, had blamed typhus and trench fever. But this new analysis paints a broader picture of disease and despair. Contaminated food and lice likely spread infection among men already half-dead from frostbite and starvation.

“In light of our results, a reasonable scenario for the deaths of these soldiers would be a combination of fatigue, cold and several diseases,” said study author Nicolás Rascovan. “While not necessarily fatal on their own, these infections could have been devastating for already weakened individuals.”

The team confirmed their findings through multiple checks, including signs of DNA decay typical of centuries-old remains. It wasn’t just science for science’s sake; it was a forensic reconstruction of human misery.

Historians have long argued over who or what defeated Napoleon. He blamed the winter. The French called it bad luck. The Russians called it strategy. Dr Michael Rowe of King’s College London thinks it’s time to give the Russians their due. “It wasn’t just the cold,” he said. “They had a good plan, clever manoeuvres and a capable army. Disease and weather only finished what their tactics began.”

So perhaps the real story of 1812 isn’t of heroism or hubris, but biology. The emperor who once thought himself invincible was undone by lice, bacteria and a few unlucky meals. The retreat from Moscow wasn’t just a military failure — it was a reminder that even empires, like men, rot from within.

You may also like

Jitan Ram Manjhi slams Tejashwi Yadav over job promise, terms it 'impractical'

Tej Pratap Yadav says Tejashwi cannot be a Jan Nayak

Huge Brit movie star's Aston Martin for sale and his umbrella is still in boot

Strictly Come Dancing LIVE: Tess and Claudia's first appearance since exit bombshell

Diwali celebration at Times Square on November 9: Timings, events, performances and all you need to know